I recently became IAPP CIPP/US certified. "What does that mean?" you ask? Good question!

What is the CIPP/US designation?

The International Association of Privacy Professionals (IAPP) is a nonprofit association of privacy professionals--the largest in the world. The IAPP issues the Certified Information Privacy Professional (CIPP) designations, which are the most recognized information privacy certifications globally. The

CIPP/US credential demonstrates an understanding of privacy and security concepts, best practices, and international norms, with a specific emphasis on U.S. privacy and information security laws. Applicants are tested to ensure they have the requisite knowledge in the following areas:

I. The U.S. Privacy Environment

A. Structure of U.S. Law

i. Constitutions

ii. Legislation

iii. Regulations and rules

iv. Case law

v. Common law

vi. Contract law

c. Legal definitions

d. Regulatory authorities

i. Federal Trade Commission (FTC)

ii. Federal Communications Commission (FCC)

iii. Department of Commerce (DoC)

iv. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS)

v. Banking regulators

vi. State attorneys general

vii. Self-regulatory programs and trust marks

e. Understanding laws

i. Scope and application

ii. Analyzing a law

iii. Determining jurisdiction

iv. Preemption

B. Enforcement of U.S. Privacy and Security Laws

a. Criminal versus civil liability

b. General theories of legal liability

i. Contract

ii. Tort

iii. Civil enforcement

c. Negligence

d. Unfair and deceptive trade practices (UDTP)

e. Federal enforcement actions

f. State enforcement (Attorneys General (AGs), etc.)

g. Cross-border enforcement issues (Global Privacy Enforcement Network (GPEN))

h. Self-regulatory enforcement (PCI, Trust Marks)

C. Information Management from a U.S. Perspective

a. Data classification

b. Privacy program development

c. Incident response programs

d. Training

e. Accountability

f. Data retention and disposal (FACTA)

g. Vendor management

i. Vendor incidents

h. International data transfers

i. U.S. Safe Harbor

ii. Binding Corporate Rules (BCRs)

i. Other key considerations for U.S.-based global multinational companies

j. Resolving multinational compliance conflicts

i. EU data protection versus e-discovery

II. Limits on Private-sector Collection and Use of Data

A. Cross-sector FTC Privacy Protection

a. The Federal Trade Commission Act

b. FTC Privacy Enforcement Actions

c. FTC Security Enforcement Actions

d. The Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act of 1998 (COPPA)

B. Medical

a. The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA)

i. HIPAA privacy rule

ii. HIPAA security rule

b. Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health (HITECH) Act of 2009

C. Financial

a. The Fair Credit Reporting Act of 1970 (FCRA)

b. The Fair and Accurate Credit Transactions Act of 2003 (FACTA)

c. The Financial Services Modernization Act of 1999 ("Gramm-Leach-Bliley" or GLBA)

i. GLBA privacy rule

ii. GLBA safeguards rule

d. Red Flags Rule

e. Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act of 2010

f. Consumer Financial Protection Bureau

D. Education

a. Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act of 1974 (FERPA)

E. Telecommunications and Marketing

a. Telemarketing sales rule (TSR) and the Telephone Consumer Protection Act of 1991 (TCPA)

i. The Do-Not-Call registry (DNC)

b. Combating the Assault of Non-solicited Pornography and Marketing Act of 2003 (CAN-SPAM)

c. The Junk Fax Prevention Act of 2005 (JFPA)

d. The Wireless Domain Registry

e. Telecommunications Act of 1996 and Customer Proprietary Network Information

f. Video Privacy Protection Act of 1988 (VPPA)

g. Cable Communications Privacy Act of 1984

III. Government and Court Access to Private-sector Information

A. Law Enforcement and Privacy

a. Access to financial data

i. Right to Financial Privacy Act of 1978

ii. The Bank Secrecy Act

b. Access to communications

i. Wiretaps

ii. Electronic Communications Privacy Act (ECPA)

1. E-mails

2. Stored records

3. Pen registers

c. The Communications Assistance to Law Enforcement Act (CALEA)

B. National Security and Privacy

a. Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act of 1978 (FISA)

i. Wiretaps

ii. E-mails and stored records

iii. National security letters

b. Uniting and Strengthening America by Providing Appropriate Tools Required to Intercept and Obstruct Terrorism Act of 2001 (USA-Patriot Act)

i. Other changes after USA-Patriot Act

C. Civil Litigation and Privacy

a. Compelled disclosure of media information

i. Privacy Protection Act of 1980

b. Electronic discovery

IV. Workplace Privacy

A. Introduction to Workplace Privacy

a. Workplace privacy concepts

i. Human resources management

b. U.S. agencies regulating workplace privacy issues

i. Federal Trade Commission (FTC)

ii. Department of Labor

iii. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC)

iv. National Labor Relations Board (NLRB)

v. Occupational Safety and Health Act (OSHA)

vi. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC)

c. U.S. Anti-discrimination laws

i. The Civil Rights Act of 1964

ii. Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA)

iii. Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act (GINA)

B. Privacy before, during and after employment

a. Employee background screening

i. Requirements under FCRA

ii. Methods

1. Personality and psychological evaluations

2. Polygraph testing

3. Drug and alcohol testing

4. Social media

b. Employee monitoring

i. Technologies

1. Computer usage (including social media)

2. Location-based services (LBS)

3. Mobile computing

4. E-mail

5. Postal mail

6. Photography

7. Telephony

8. Video

ii. Requirements under the Electronic Communications Privacy Act of 1986 (ECPA)

iii. Unionized worker issues concerning monitoring in the U.S. workplace

c. Investigation of employee misconduct

i. Data handling in misconduct investigations

ii. Use of third parties in investigations

iii. Documenting performance problems

iv. Balancing rights of multiple individuals in a single situation

d. Termination of the employment relationship

i. Transition management

ii. Records retention

iii. References

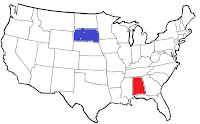

V. State Privacy Laws

A. Federal vs. state authority

B. Marketing laws

C. Financial Data

a. Credit history

b. California SB-1

D. Data Security Laws

a. SSN

b. Data destruction

E. Data Breach Notification Laws

a. Elements of state data breach notification laws

b. Key differences among states

Why did you decide to get the CIPP/US certification?

More and more people are claiming to be privacy experts these days, including a number of lawyers. Although very few law firms advertised a privacy practice group as of just a few years ago, almost all

large law firms do now...with varying degrees of credibility. Some lawyers are holding themselves out as privacy experts when their expertise is limited to a couple of privacy laws and a specific context. They are nonetheless re-branding themselves as "privacy" lawyers. While there certainly are more lawyers who are competent in a range of privacy and information security issues than ever before, they remain few and far between. The CIPP/US certification is perhaps the best way to

clearly and immediately demonstrate an understanding of the core concepts and legal issues of privacy and information security.

Does the CIPP/US designation guarantee expertise?

The CIPP/US designation does not guarantee expertise in any particular area of privacy law. The certification tests (there are currently two) do not require the depth of understanding that a true expert must have. For example, the study guides and tests cover financial privacy issues at a level of depth just beyond the surface. There is much more to know about financial privacy law and practice. However, the CIPP/US designation does provide assurance that the certificate holder is at least aware of the salient issues and knows where to find answers or guidance, and those two items are very important. Furthermore, certification requires ongoing learning. Mainting IAPP CIPP certification requires the holder to fulfill 20 hours of continuing privacy education (CPE) per two-year period, to ensure the holder's knowlege remains up to date.

The CIPP/US certification is no guarantee of true legal expertise, but it does provide an independent confirmation of basic competence across a broad spectrum of privacy and information security law. It also tells you that the holder is continuing to build upon his or her knowledge in these areas.

* The N.C. State Bar, the regulatory body that supervises and disciplines lawyers licensed in North Carolina, prohibits a lawyer from using the term "specialized" to describe anything other than a N.C. Bar-issued certificate of specalization in one of a very limited number of fields of law. There is no specalization certificate available from the N.C. State Bar for privacy, information security, or any related field of law.

There are a number of surveys and studies published each year that provide empirical data about the cybersecurity landscape. One of them is the Verizon Data Breach Investigations Report, which compiles publicly-reported breaches with other sources (including intelligence gathered by the Verizon Threat Research Advisory Center). The 2020 DBIR has just been published. This year, Verizon amassed 157,525 incidents and 108,069 breaches. Here are some interesting findings:

There are a number of surveys and studies published each year that provide empirical data about the cybersecurity landscape. One of them is the Verizon Data Breach Investigations Report, which compiles publicly-reported breaches with other sources (including intelligence gathered by the Verizon Threat Research Advisory Center). The 2020 DBIR has just been published. This year, Verizon amassed 157,525 incidents and 108,069 breaches. Here are some interesting findings: